Let’s be realistic: moving over to Linux can be daunting, so you’ll need as much help as you can get. These are the things that would have helped me the most when I transitioned from Windows.

1

The Difference Between a Terminal, a Shell, and the Command Line

One of the most confusing things when starting with Linux is the terminology. Some people will use terms interchangeably, while others insist on the exact correct usage. Unless you’re aware of the differences between terms, it’s easy to make mistakes.

Here’s how I remember this: the terminal is an app that runs a shell, which provides a command line.

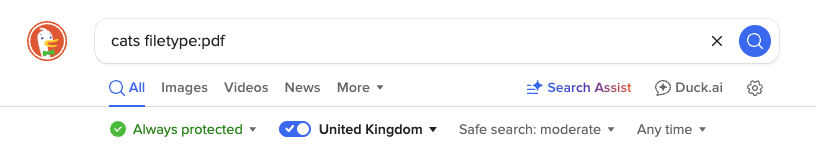

A command-line interface (CLI) is a text-based alternative to a graphical user interface (GUI). It shows a prompt for command input, which you’ll type with the keyboard, then press Enter to run. You can find a command line in several different apps: an IDE, your browser’s console, or a Unix shell. Even a web search box can be considered a very specific type of command line.

A shell provides a command-line interface. There are many different types of Unix shells, reflecting the operating system’s long history. The most commonly used are Bash and Zsh, with other examples including Fish, Ksh, and Tcsh. The shell provides core functionality that sits at a higher level than the operating system’s kernel. It provides a command language that you can use to run and manage programs.

The terminal (strictly, terminal emulator) is an app that runs a shell, passing input to it and displaying output from it. It is often a GUI app, with windowing features like tabs and copy/paste using the mouse. Terminals available on Linux include Kitty, Terminator, Guake, and Ghostty. On macOS, iTerm2 is very popular. A terminal was originally cheap, standalone hardware that provided a keyboard and display to connect to a computer. You may also hear the term “console,” which is roughly analogous to “terminal.”

I’ll continue to use the word terminal throughout this article to refer to the general use of a shell command line.

2

How to Find Help

It’s common to be left feeling a bit in the dark when you start using the terminal. An empty prompt, with no clear guidance or list of available options, can be pretty intimidating.

On Linux, help begins with man, the manual browser. This command gives access to text-based documentation on almost every command you can run in the terminal. You can pull up help pages by running man

$ man ls

$ man mkdir

$ man man

This will display an appropriate manual page using your system’s pager, a command that displays text in a paged interface, with features to scroll up and down, search for text, and more. Usually, the default pager will be less and you can use it to scroll the manual with Up/Down cursor keys or one page at a time with Space. Press q to quit or h for more help.

The man page documentation is detailed and technical, but it’s comprehensive too. Man pages have a pretty standard layout, with sections on command options, configuration, and examples.

The best way to familiarize yourself with them is to read them, and I recommend starting with simpler, shorter pages for common commands like pwd, mkdir, and echo. The ls command is a good example of a very common program with a long man page that is excellent for getting to know the system.

You can even try man man if you’re struggling to use man, but its documentation is fairly complicated, so it may not be all that helpful!

If man pages seem a little daunting, you could try tldr instead. This alternative needs to be installed, but it’s friendlier than man, with a focus on examples of how to use the command for common cases.

3

How Aliases Could Save Me So Much Time

I didn’t realize how much time I was wasting until I started using aliases. An alias is like a shortcut for a command, and it has two main advantages, which will give big wins in the long term:

- An alias is usually shorter, saving you the time and effort of typing more characters.

- An alias helps you avoid having to remember complex options.

I’ve seen some people use aliases like this:

alias ll="ls -l"

Which is great because it saves you typing three characters every time you want to list files, which is something you’ll do a lot. This alias effectively creates a new command: ll.

But, for me, the second benefit is more significant. Command-line options can be really tricky to remember, especially since they’re not always consistent between programs. So, when I find an option I’d like as the default, I just update an alias for that command, and I never have to remember the details:

alias ls='ls -GF'

This gives me two nice improvements to ls: colorized output and symbols that identify different file types, like directories or symlinks. There’s no new command here, so I just go on using ls as I always have, it’s just a slightly better version.

4

Everything About Command Chaining

You may already know how to run a command by now, but how much do you know about running multiple commands at once?

The most common form is probably the pipe, because it is so useful for everyday tasks. A pipe runs two commands at the same time, passing the output from one as the input to the other:

ls | wc -l

This command line prints the number of files in the current directory. Piping employs Linux’s use of text as the primary means of data exchange, and it dramatically increases the utility of simple commands that do one thing well. But there are other ways of running multiple commands, like the semicolon:

sleep 5; echo done

This will run the sleep command, then echo, so you’ll see a pause, then the output from echo. Contrast this with:

sleep 5 | echo done

Because a pipe runs commands simultaneously, you’ll see output from echo immediately, then a pause. The echo command ignores any input sent to it, which doesn’t matter much anyway since sleep doesn’t produce output.

You can even use logical operators to run a command based on the success of another:

sleep 5 && echo that worked

The && means “keep running commands only if the previous one succeeded,” and it’s particularly useful during software compilation, as in this very common pattern:

make && make install

Here, make builds a program from source, while make install copies the final program to a known location. There’s no point trying to install it if compilation fails, so this command line handles both success and failure.

5

How Commands Can Run in the Background and How to Manage Them

There’s something about running multiple commands, some of them in the background, that’s another tricky concept to grasp. I think it’s because the command line appears to be so focussed on one line at a time, one command at a time. But this is a misconception that you need to quash early on in your Linux journey.

Of course, most of the more common commands—ls, mkdir, cat—make a lot of sense running in the foreground: they’re quick to run, and you’ll usually want their results immediately. But as soon as you need to compile a program or start a long-running program, you’ll start wondering about job control—before you even know the term.

The concept of a job is yet more confusing terminology that is almost, but not quite, synonymous with program, command, or process. A job can be a single process, but it can also be a group of processes, i.e., anything that you start from a single command line.

With job control, you can start running something, then move it to the background while you work on something else. You can think of it a bit like minimising a window in a GUI. What’s more, you can pause the job, restart it, move it back to the foreground, or kill it altogether.

[maybe make the following a screenshot??]

To suspend a job that’s currently running, just press Ctrl + Z:

$ du -skh /

^Z

zsh: suspended du -skh /

Note that the shell—zsh, in this case—reports that the job has been suspended, which means it pauses. You can resume the job in the background, or bring it back to the foreground, but you’ll need its id first. To obtain that, use the jobs command:

jobs

You’ll see a list of all the jobs that have not yet finished, alongside their status:

Each job has an assigned number which you can use to foreground it, using the fg command:

$ fg %5

You can also start a command running in the background by adding an ampersand to the end:

du -skh / &

6

How the PATH Works and Why It’s So Useful

Most lessons I’ve learned about Linux boil down to “it’s easier than you think,” even when the opposite seems true at first. The PATH is a prime example.

If you’ve come from the Windows world, you might think that installation is a complex process, involving specific paths, rigid filenames, and carefully copied library files. On Linux, this really isn’t the case. Most of the time, you can run an executable program just by typing a path to it:

./my-local-program

/usr/bin/htop

This is fine, but it’s not very convenient, so there’s a shortcut. The PATH environment variable stores a set of directories that your shell will search when you try to run a command that doesn’t include any path components, e.g.

htop

In this case, if your PATH looks something like “/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin,” your shell will look for the following programs:

- /usr/local/bin/htop

- /usr/bin/htop

- /bin/htop

This is a convenience, but the same system also lets you install custom versions of software. The order of directories in your PATH is significant, so the first program that’s present will be the one that’s used. This means you can have a default version in /bin and a user-installed one in /usr/bin, and the latter one will be favoured, as you’d expect.

7

How to Use Hidden Files in My Home Directory

The Linux terminal is full of cases where you can configure things as you see fit, from aliases to your PATH and beyond. Another example is the XDG Base Directory Specification, which is a long-winded way of referring to a set of known files and directories in your home (user) directory.

The spec is useful because it lets you store user-specific files in a standard way, so that other programs can rely on them. Before the spec, various files—like configuration, data, and even programs—would tend to litter your home directory, potentially conflicting and causing all sorts of problems.

Using XDG, they can all be gathered in hidden locations. The Linux system of treating files that begin with a period as hidden files enables this, and it’s another aspect of the OS that’s really useful to grasp early on.