Tech companies once launched products without fear of Twitter roasts or YouTube takedowns, throwing experimental gadgets at consumers like digital darts at a moving dartboard. The 1990s belonged to risk-takers who weren’t afraid of spectacular public failure.

These weren’t merely corporate face-plants—they were expensive lessons that taught the industry how not to build the future. Every smartphone, gaming console, and streaming device you love today learned something from these magnificent disasters. Sometimes breakthrough innovation requires breaking everything first.

22. Sony Magic Link (1994)

Checking your calendar shouldn’t require navigating a virtual small town, but Sony’s $999 Magic Link made simple tasks feel like geographical expeditions. The Magic Cap OS represented everything as buildings and rooms, backed by AT&T and Sony despite proving that skeuomorphism has hard limits when taken to ridiculous extremes.

Revolutionary interface concepts work best when they don’t require learning entirely new metaphorical geography for basic computing tasks. Sometimes innovation means knowing when familiar is better than cleverly different, especially at premium prices.

21. Nintendo Virtual Boy (1995)

If you were excited about virtual reality in 1995, the Virtual Boy delivered headaches faster than immersion with its red-tinted monochromatic display. Players hunched over this tabletop “portable” system for $179, squinting at graphics that made original Game Boy screens look revolutionary by comparison.

Nintendo killed it after just seven months, but this early VR experiment provided valuable lessons for today’s Oculus and PlayStation VR systems. Sometimes pioneering new technology means enduring public embarrassment while learning what definitely doesn’t work.

20. Crystal Pepsi (1992)

Transparent cola that tasted like Pepsi confused consumers who expected Sprite-like flavors from clear beverages. Despite massive marketing including Van Halen Super Bowl commercials, people couldn’t reconcile the visual-taste disconnect at $1.79 per bottle, proving that fighting cognitive dissonance rarely wins.

At $1.79 per bottle, Crystal Pepsi lasted roughly a year before disappearing into nostalgic novelty territory. Visual expectations drive taste perception—fighting cognitive dissonance rarely wins, regardless of marketing budget size or celebrity endorsements.

19. Atari Jaguar (1993)

Gaming’s first 64-bit console boasted cutting-edge specs but featured a controller that resembled a calculator superglued to a gamepad. At $249, the Jaguar undercut competitors on price but delivered a game library thinner than airplane coffee and twice as disappointing.

Atari’s final console roared onto shelves and meowed its way to clearance bins within months of launch. Complex controllers don’t equal innovative gaming—sometimes simple, intuitive design wins over engineering showboating and marketing gimmicks.

18. Apple QuickTake (1994)

Apple’s $749 entry into digital photography captured eight photos at postage-stamp resolution, making every memory look like it was filtered through a potato. The QuickTake resembled binoculars crossed with a toaster, forcing users to choose between quantity and quality while receiving neither.

Despite obvious shortcomings, QuickTake helped normalize filmless photography for everyday consumers when digital cameras were still mysterious. Apple learned crucial lessons here before eventually creating the camera technology that killed the dedicated camera industry entirely.

Nostalgic for the vintage era of digital and electronic gadgets? Stroll further down memory lane with this list of iconic 70s gadgets that were way ahead of their time.

17. Nokia N-Gage (2003)

Converged devices needed to excel at multiple functions, but the N-Gage failed at both gaming and calling for $299. Making calls required holding the device’s edge to your ear like a taco, earning the “taco phone” nickname that defined its market identity more than any marketing campaign.

Changing games meant removing the battery, because Nokia apparently thought inconvenience was a desirable feature worth engineering into their product. Combining two products successfully requires mastering both individually first—hybrid disasters result from compromising everything to achieve nothing.

16. Tamagotchi (1996)

Digital responsibility came in $17.99 packages when Tamagotchi sold over 82 million units while creating classroom chaos worldwide. Schools banned these electronic pets after classrooms turned into digital zoos, and parents questioned why children formed emotional attachments to pixelated creatures that inevitably died from neglect.

Success and cultural impact don’t always align—sometimes your biggest commercial hit becomes everyone else’s biggest headache to manage. The Tamagotchi taught kids about responsibility and mortality when their digital pets inevitably died from neglect or low batteries.

15. Philips CD-i (1991)

Interactive multimedia systems need clear identity, and the CD-i’s confusion between gaming console and educational tool cost around $700. Neither fish nor fowl, it’s mostly remembered for producing infamously poor Legend of Zelda games that Nintendo pretends don’t exist in their official timeline.

The controller design made using chopsticks for the first time feel intuitive by comparison, frustrating users at every interaction. Jack-of-all-trades products often master nothing, especially when they cost premium prices for mediocre experiences across multiple categories.

14. Amiga CD32 (1993)

Competitive specs and decent third-party support made the CD32 a promising console at $399—until corporate bankruptcy killed its potential overnight. Commodore declared bankruptcy in April 1994, just months after launch, making this console gaming’s equivalent of a posthumously published novel.

Potentially great but tragically cut short, the CD32 proved that timing matters more than technology when your parent company disappears. Even the best products can’t survive corporate death, regardless of their technical merits or market potential.

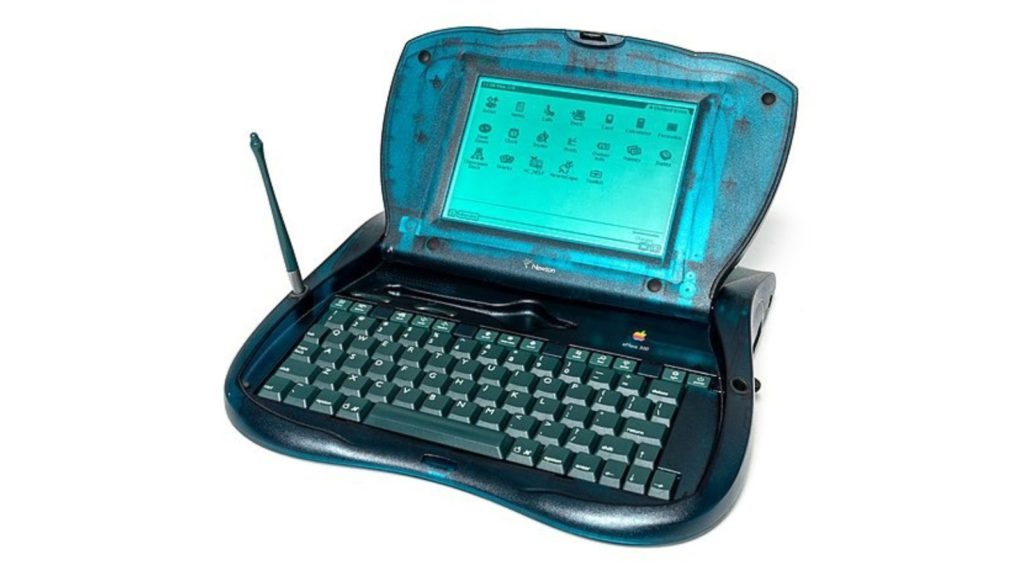

13. Apple Newton MessagePad (1993)

Newton Message Pad’s handwriting recognition turned grocery lists into abstract art and “call mom” into incomprehensible squiggles that would baffle archaeologists. At $700 (roughly $1,400 today), this digital notepad cost more than most people’s monthly rent while providing entertainment value through its spectacular misinterpretations.

Doonesbury comics mocked it mercilessly, and The Simpsons turned it into cultural shorthand for tech failure. Yet this expensive disaster pioneered the entire PDA category and planted essential seeds for the iPhone revolution 14 years later.

12. 3DO Interactive Multiplayer (1993)

Trip Hawkins’ $699 multimedia console demanded luxury car money while competitors offered Honda performance at Honda prices. The 3DO boasted impressive technical specifications that required taking out loans for slightly better graphics than systems costing half as much.

Celebrity endorsements from characters like Gex the Gecko couldn’t convince consumers to mortgage their entertainment budgets for marginal gaming improvements. Technical superiority means nothing when your price point lives in fantasy land while competitors occupy reality.

Not every bold idea of the 90s turned out to be a winner, despite many vintage tech fails from earlier serving as cautionary tales.

11. DAT (Digital Audio Tape) (1987-1993)

If you wanted CD-quality recording in compact cassette format, DAT delivered everything except industry support and reasonable pricing. Professional recorders cost over $1,000, and music industry lobbying ensured DAT remained niche instead of becoming the next-generation Walkman it should have been.

Superior technology means nothing when entire industries unite against your success through coordinated legal and financial warfare. Sometimes the best product loses to politics, proving that technical excellence can’t overcome organized opposition.

10. RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc (1981-1986)

SelectaVision’s capacitance technology read video from vinyl-like discs at $500 per player and $15-25 per disc during VHS’s market dominance. Launching analog solutions against digital competitors was like bringing a horse-drawn carriage to Formula 1 racing—technically impressive but hopelessly outdated.

The technology was obsolete before most consumers even knew it existed, launching outdated solutions during rapid industry evolution. Superior engineering means nothing when your entire approach becomes irrelevant while you’re still explaining how it works.

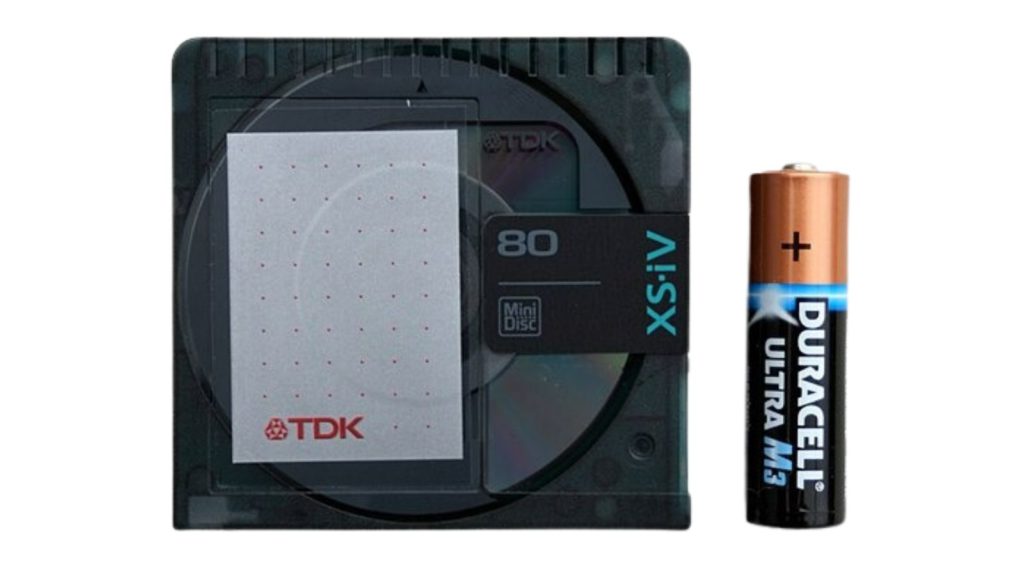

9. Sony MiniDisc (1992)

Superior audio technology met market indifference when Sony’s MiniDisc offered CD quality in smaller, more durable packages for $750 players and $14 discs. This format should have dominated portable music with practical advantages over both CDs and cassettes, but proprietary approaches often lose to open standards.

Sony’s proprietary approach and MP3’s rise relegated this technically superior format to cult status in America while achieving moderate Japanese success. Technical superiority loses to open standards and convenience—proprietary brilliance often dies in isolation regardless of engineering quality.

8. Iomega Zip Drive (1994)

Portable storage reliability matters more than capacity, but Zip Drives destroyed user data so consistently they spawned class-action lawsuits. The drive cost $199 with 100MB disks at $20 each, making data storage expensive before making it disappear entirely through the infamous “click of death.”

The infamous “click of death” sound meant your files vanished forever, teaching an entire generation about backup importance the hardest way possible. Reliability matters more than capacity when your storage solution randomly eats everything users trust it to protect.

7. Apple eMate 300 (1997)

Schools couldn’t afford the eMate 300’s $800 price tag, and professionals found its Newton-powered capabilities too limited for serious work. This translucent green clamshell device sat awkwardly between education and business markets, satisfying neither while burning through Apple’s development budget.

Its distinctive translucent design directly influenced the iconic iBook aesthetic that would define Apple’s laptop identity for years. Good design ideas rarely die at Apple—they hibernate until technology and market timing align perfectly.

6. IBM Simon (1994)

Smartphone innovation arrived 13 years early with the IBM Simon, weighing nearly a pound while offering battery life measured in minutes rather than hours. At $899 plus cellular service, using Simon in public made you look like you were making calls on a brick while everyone else used normal phones.

Its touchscreen and apps were revolutionary concepts trapped in prehistoric execution that punished early adopters for their enthusiasm. Being first with breakthrough concepts doesn’t guarantee success when your execution feels like technological masochism rather than advancement.

5. Microsoft Bob (1995)

Folders were apparently too complicated for computer users, according to Microsoft’s $99 software that transformed desktops into virtual houses with cartoon helpers. Bob treated users like toddlers who needed animated guidance for email and file management while insulting their intelligence daily.

Bob’s legacy lives through Comic Sans font and as a cautionary tale about condescending interface design that assumes customers are idiots. Helpful features become harmful when they prioritize showing off over actually helping users accomplish their goals efficiently.

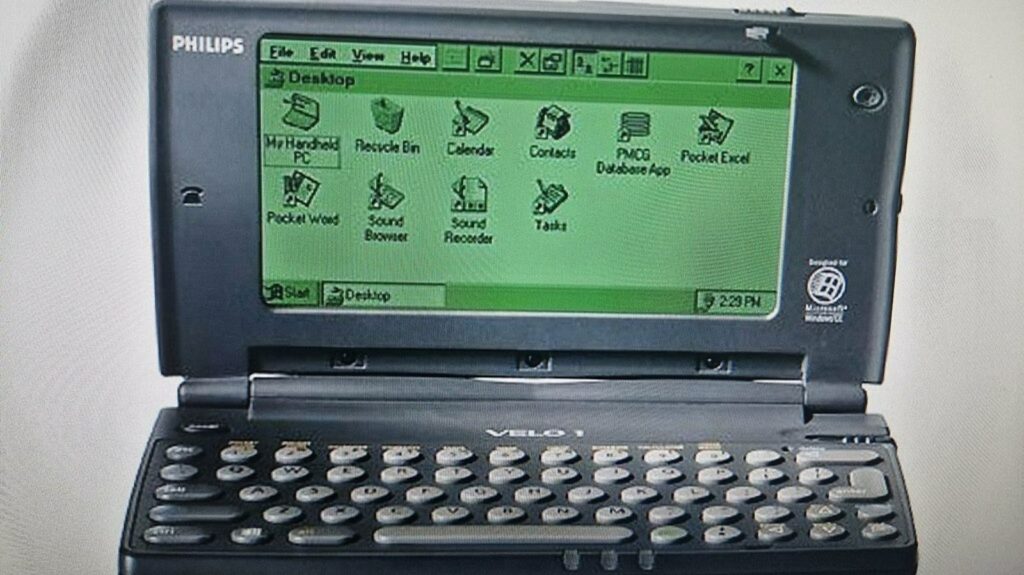

4. Philips Velo 1 (1997)

Windows CE devices promised desktop functionality in portable form, but the Velo delivered frustration when Windows CE barely ran itself. Despite featuring decent hardware including a keyboard that wasn’t completely terrible, it launched precisely when Palm was perfecting the PDA formula with simpler solutions.

Market timing can kill superior products faster than technical flaws—being right too late often equals being wrong entirely. The Velo learned that lesson expensively while Palm dominated the PDA market with simpler, more intuitive solutions.

3. Clippy (1997)

Workplace productivity crashed into digital harassment when Microsoft Office bundled this animated paperclip with every installation. Clippy interrupted work with toddler-like persistence, offering unwanted advice at precisely wrong moments throughout the day while becoming universally despised for turning assistance into annoyance.

Every interruption felt like digital nails on a chalkboard, proving that timing matters more than helpfulness in software design. Good intentions can’t save features that fundamentally misunderstand when and how users actually want assistance with their work.

2. Apple Pippin (1996)

At $599, Apple’s gaming console sold fewer than 42,000 units worldwide while PlayStation and Nintendo 64 dominated the market. Bandai manufactured this digital disaster, but even their gaming expertise couldn’t save Apple’s misguided console ambitions from marketplace reality.

The Pippin proved Apple belonged in computers, not gaming, delivering an expensive lesson that kept the company focused on their strengths. This failure prevented future gaming misadventures until the iPhone turned everyone into mobile gamers without Apple realizing it.

1. Tamagotchi (1996)

Digital responsibility came in $17.99 packages when Tamagotchi sold over 82 million units while creating classroom chaos worldwide. Schools banned these electronic pets after classrooms turned into digital zoos, and parents questioned why children formed emotional attachments to pixelated creatures that inevitably died from neglect.

Success and cultural impact don’t always align—sometimes your biggest commercial hit becomes everyone else’s biggest headache to manage. The Tamagotchi taught kids about responsibility and mortality when their digital pets inevitably died from neglect or low batteries.