We all know marketing is often misleading, but you might not realize how many common tech marketing terms are unclear or even untrue. Keep an ear open for these terms that don’t mean what they seem.

5

“Military-Grade”

“Military-grade protection” is a term often used by manufacturers of phone cases and similar protective hardware to suggest that their goods can survive combat conditions. You may also hear a VPN or secure messaging app uses “military-grade encryption” to protect your data.

In reality, this phrase is meaningless for several reasons. First, there’s no universally agreed-upon standard for what “military-grade” is. Any company can claim this because there’s no objective test like there is for a device’s water resistance.

Second, the idea that “military-grade” means the absolute highest quality possible isn’t accurate either. Militaries usually aren’t looking for the best money can buy; they prioritize equipment being durable, straightforward to use, and affordable enough to buy for large groups of people. Taken that way, a “military-grade” phone case would mean reliable yet unremarkable—not necessarily bad, but not what marketers are going for either.

When applied to software security instead of physical items, “military-grade encryption” is also misleading. The encryption that the military uses for classified info is the same AES-128 or AES-256 encryption your browser uses to secure your login to sensitive sites, or chat apps like WhatsApp use for end-to-end encryption. These are standard encryption protocols; there’s nothing special about the military using them.

4

“Waterproof”

Since liquid is one of the most common sources of device destruction, having a waterproof phone or smartwatch sounds like a good idea. And while this term isn’t outright false, it does come with an important caveat: nothing is truly “waterproof”. Under the right circumstances, water will enter any device.

A more accurate term is “water-resistant”. We’ve explained water resistance at length; in summary, there is a standard test called IP (International Protection) that tells you how dust- and water-resistance devices are. The second digit tells you how water-resistant the device is, from a low of 0 (no resistance) all the way up to 9 (resistance to hot, high-pressure water sprays).

Most phones have a water IP rating of 7 or 8. The former means it can survive submersion in one meter (3.3 feet) of water for 30 minutes, while the latter must be greater than this and is usually specified by the manufacturer.

Always look for the IP rating, since “waterproof” doesn’t have a standard meaning. You should also beware of generic statements like “swim-proof”, especially on cheap devices. If the company doesn’t name a specific IP rating, you should assume it won’t withstand water at all.

3

“Lifetime” Licenses

Getting a one-time paid license for an app sounds great, especially in the age of constant subscriptions. Every company wants ongoing revenue to support development, so if every customer paid just once for life, the company would go out of business. This is why you’ll often see “lifetime” offers from new companies that don’t realize what a bad value this is for them.

Related

Lifetime vs. Perpetual License: What’s the Difference?

When you buy a software license, what exactly are you getting?

It’s thus unwise to take “lifetime” subscriptions at face value. The most important factor is that the “lifetime” is the software’s, not yours. The owner could decide to shut down the app at any time, making your license worthless. Other “lifetime” subscriptions state in the fine print that they only last a certain length of time, or that you have to renew them every so many years.

And even if the app stays up, the company behind it can pull all kinds of tricks to get out of it. After VPNSecure was purchased by a new owner, those who had “lifetime” licenses were informed these would no longer be honored, and they had to sign up for a new plan. In 2019, I bought a “lifetime” license for the email app Mailbird, but when the company released Mailbird 3.0, I was informed this wasn’t part of my license. I’d have to pay for a new subscription if I wanted all its features (many of which were free in the prior version).

As a modern example, I looked for “lifetime” VPNs and found one called FastestVPN, which I had never heard of before. An immediate red flag is the fake countdown on the homepage for its latest “deal”: a “New Year exclusive offer” (in May, when I visited). I examined the terms of service and there’s no mention of the “lifetime” plan, so there’s no guarantee how long this would last.

I got a lifetime license to Malwarebytes some 10 years ago, which is still honored. But that’s the exception and not something you should expect. You’re better off using the free trial or signing up for a month to see if you like the service, then paying yearly to get the discount.

2

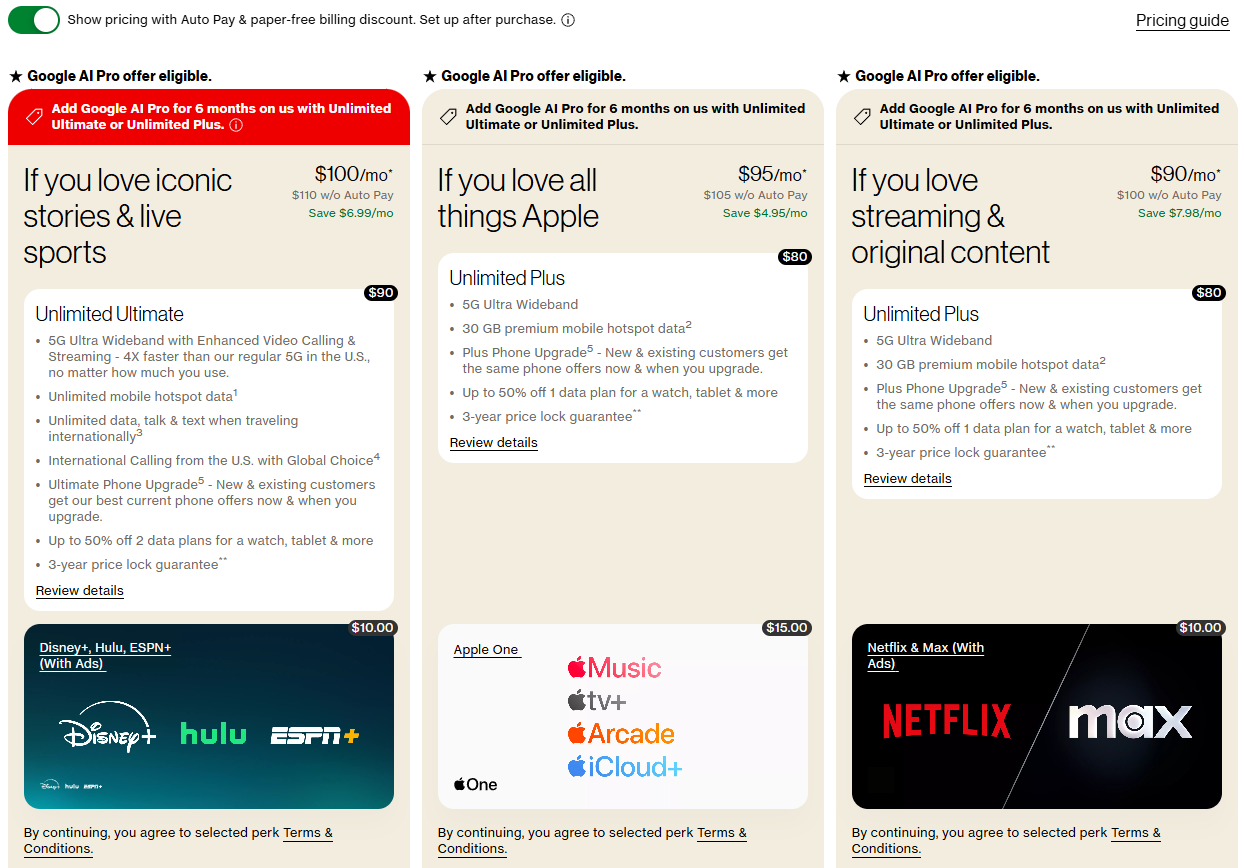

“Unlimited” Plans

These are similar to the above: having “unlimited” mobile data or cloud storage space sounds great, but there’s almost always a limit in the fine print.

Most unlimited phone plans give you a budget of 5G data, then drastically decrease the speed once you pass the threshold. For example, those on the lowest tier of T-Mobile’s Unlimited plan (Essentials) “may notice speeds lower than other customers and further reduction” when they’ve used more than 50GB of data in a month.

You’re also limited to streaming video at 480p in most cases, so you don’t even get to choose how to spend your “unlimited” data. Verizon’s “unlimited” plans don’t include unlimited hotspot data unless you pay for the top tier—meaning you’ll need to ration your hotspot usage.

Only a small percentage of people use 50GB of mobile data in a month, so these limits might not bother you. But as we’ve seen, you’re not getting exactly what the catchy slogans claim.

This isn’t limited to mobile data, either. OneDrive once offered unlimited storage for Office 365 subscribers, but changed this in 2015. The stated reason was that “a small number of users” backed up entire movie collections to OneDrive, taking up dozens of terabytes. All it took was a few people going to the extreme to prove the plan wasn’t “unlimited” after all.

1

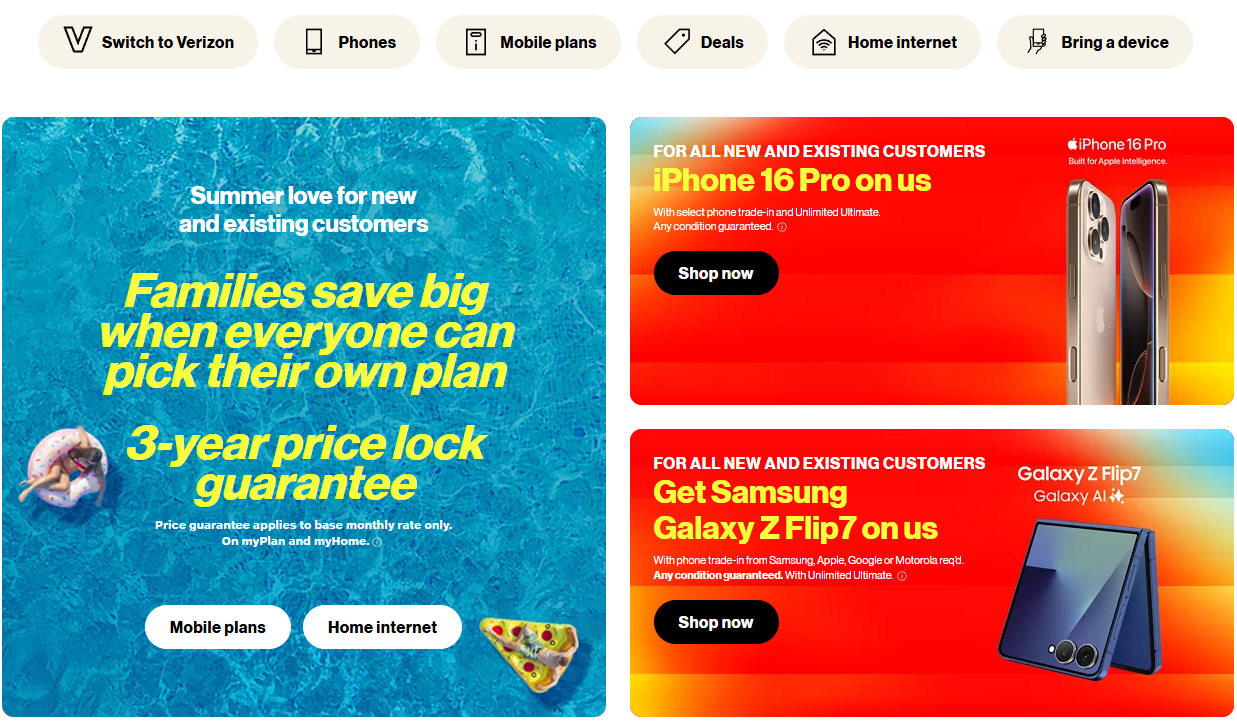

Free “On Us” Devices From Mobile Carriers

Major mobile carriers like Verizon constantly advertise that if you sign up for one of their plans, they’ll give you a phone “on them”. And while you do technically get a device without having to pay for it, the associated costs mean you end up paying more overall (and are locked into their service).

These “on us” deals generally refund the cost of a phone as bill credits over a 24- or 36-month period. Every month, you’ll see a charge for the phone and an equal reversal amount on your bill, making the phone no-cost as long as you stay the whole time.

However, what isn’t as obvious is that you need to sign up for one of the most expensive plans to get a “free” phone. Verizon’s homepage, for example, advertises the “iPhone 16 Pro on us”, where the fine print clarifies that this only applies to the 128GB model, you must sign up for the top Unlimited Ultimate plan (which costs at least $90/month before taxes and fees), and trade in a phone from certain manufacturers.

Additionally, the company is free to raise its fees or cost of service during the period, so you’re stuck for years if they want you to pay any more. And if you decide you want to go to another carrier, you have to pay off the cost of the phone and lose any remaining credit from the “free” device.

Generally, you’ll save money and have more flexibility by buying your phone directly from Apple or another manufacturer (upfront or using the payment plan), then going with a cheaper MVNO carrier like Mint Mobile.

Marketers use all kinds of confusing terms to get you to spend more money than you intended, not understand what exactly you’re paying for, or put you on the hook for future purchases. Many of the terms you see in tech product ads and on purchase pages have no clear meaning or are completely misleading.

Always read the fine print for more specific details, because they expect most people to make a quick decision from the product name or the front of the box alone.