You can program without programming tools, and integrated development environments (IDEs) are popular among developers. I take a different approach. I treat my Linux system, with its array of programming tools, as an IDE in itself.

One Window for One Job

IDEs are popular among developers because they provide access to all their tools, including an editor, an interpreter or compiler, a debugger, and even documentation. I can see why most developers would want their tools all in one place. I think I can achieve a similar experience by having separate apps in the Linux environment.

I like the idea of the Unix philosophy, of one small tool doing one job well. It may not be easy to achieve in practice, but I think it’s something that’s worth striving for.

Related

What Is Unix, and Why Does It Matter?

Most operating systems can be grouped into two different families.

It’s telling that IDEs have thrived most on non-Linux or Unix platforms, particularly Windows. Windows has made less use of command-line tools, and launching processes is resource-intensive, so there’s an incentive to favor larger programs that do more, including larger development systems.

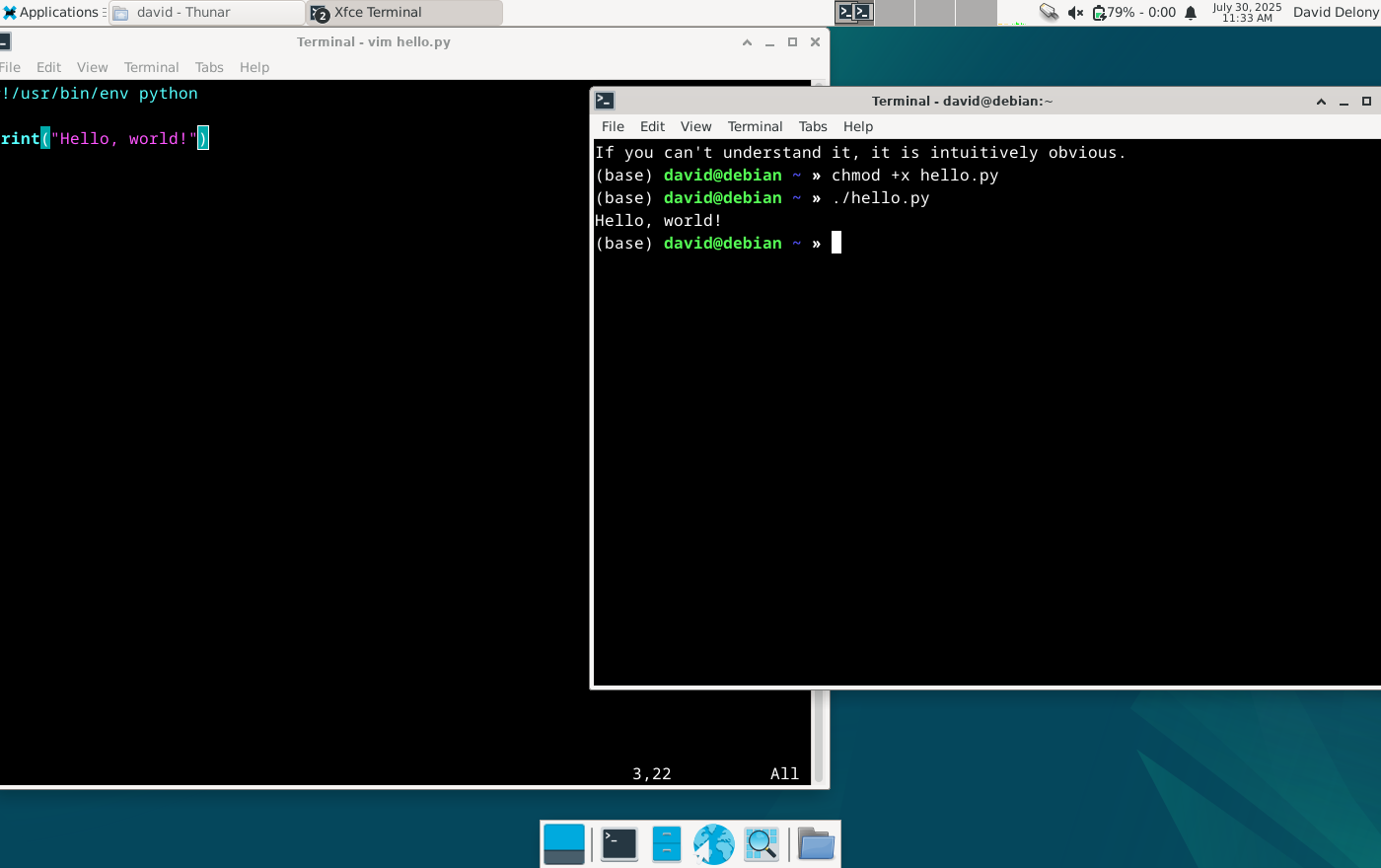

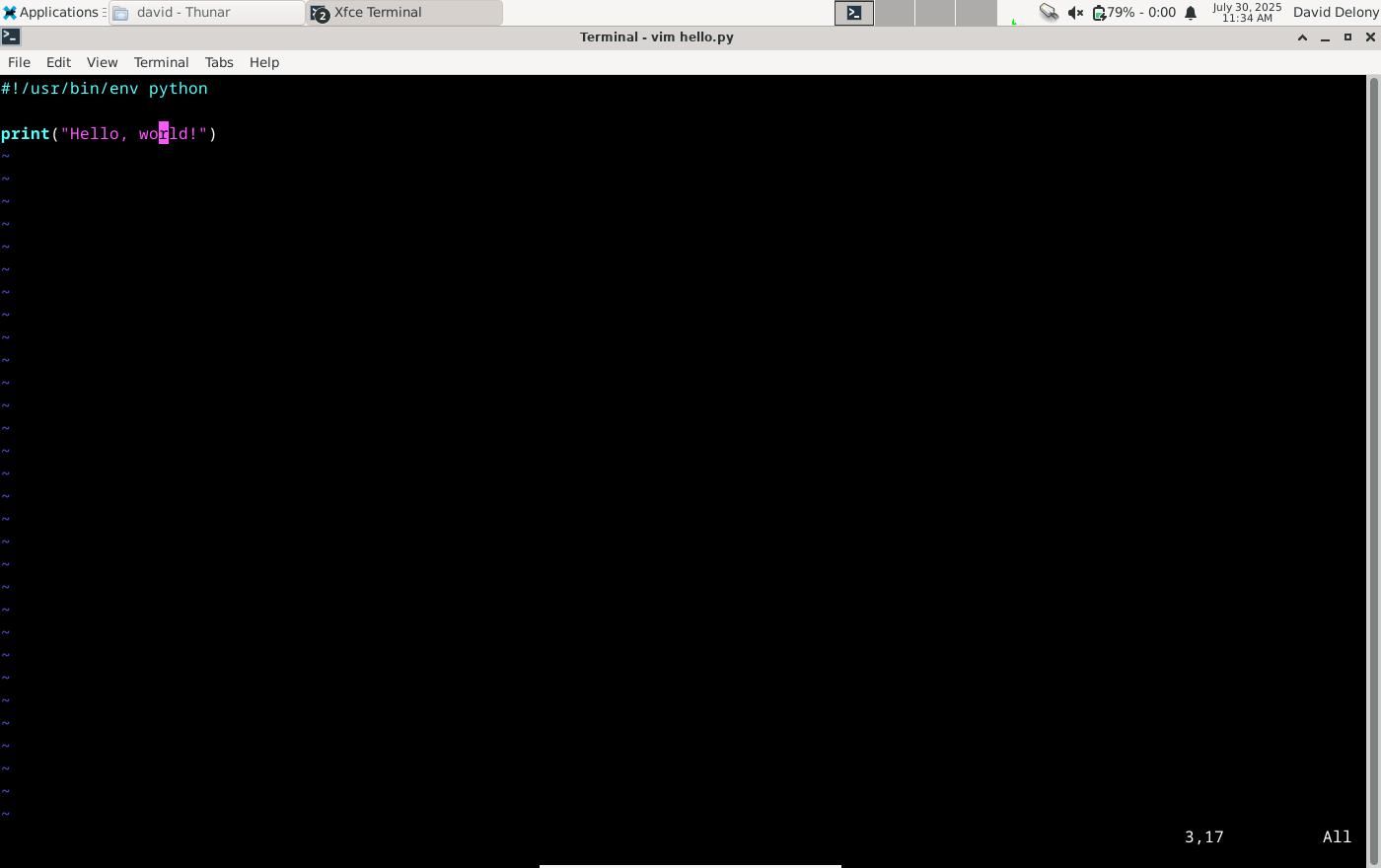

The traditional Unix approach of separate programs works well for me. I can have one shell window running Vim, another to test the program, and the other to run file manipulation programs. I can get the effect of an IDE with nimbler, smaller programs instead of one big one.

If I need to run some other task, I can just pop open another terminal window and run it without skipping a beat.

My Workflow Is Better Suited to Separate Apps

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not a professional programmer. Programming isn’t my occupation, but it’s a fun and stimulating hobby. While IDEs are suited to pro developers, my use is different than a lot of other “real” programmers.

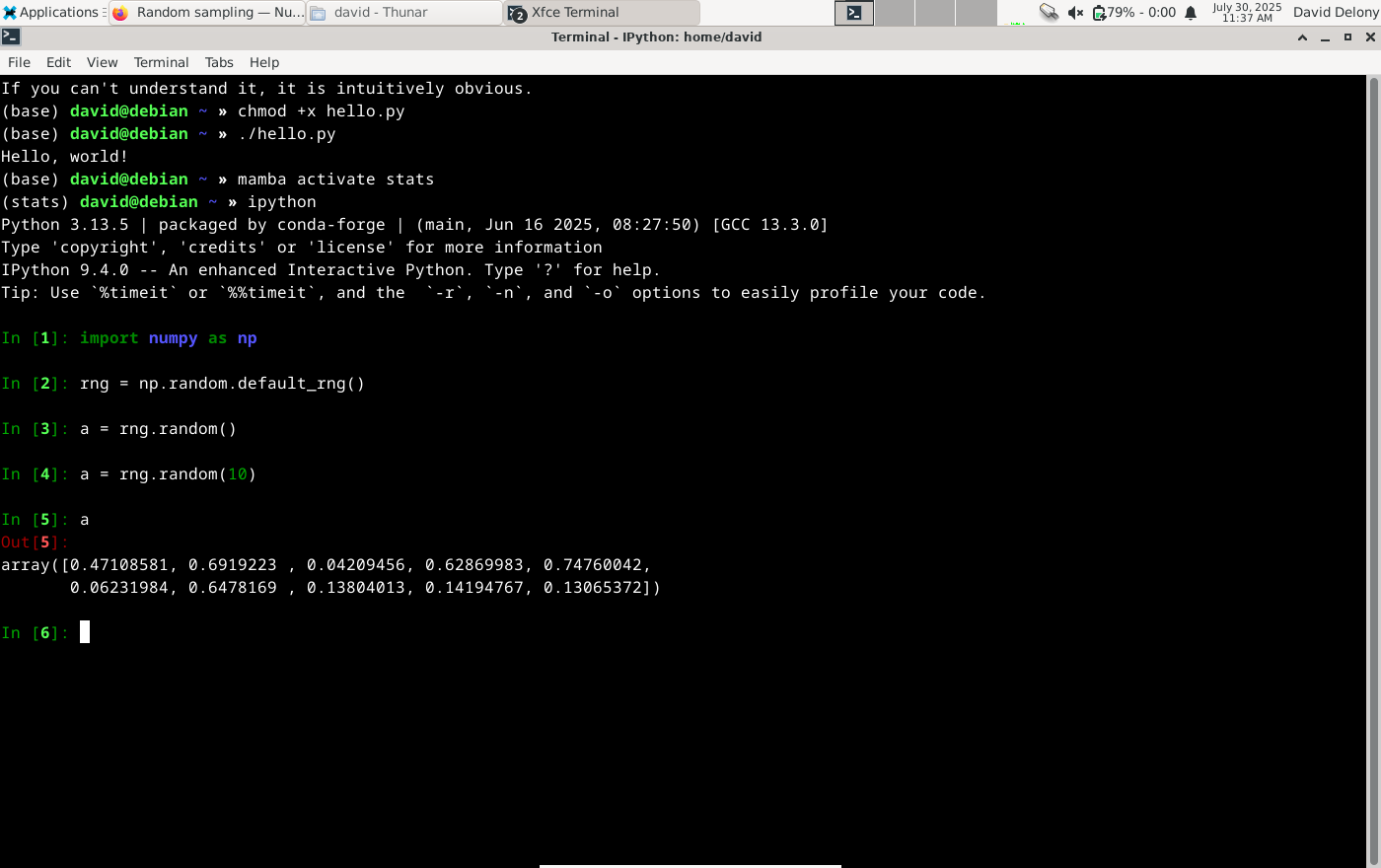

Python is my language of choice, and I tend to write smaller scripts or use interactive Python. This means either the default interactive interpreter or IPython. I’m one of those people who uses Python as their desk calculator. I don’t need to fire up a whole IDE just to do some arithmetic.

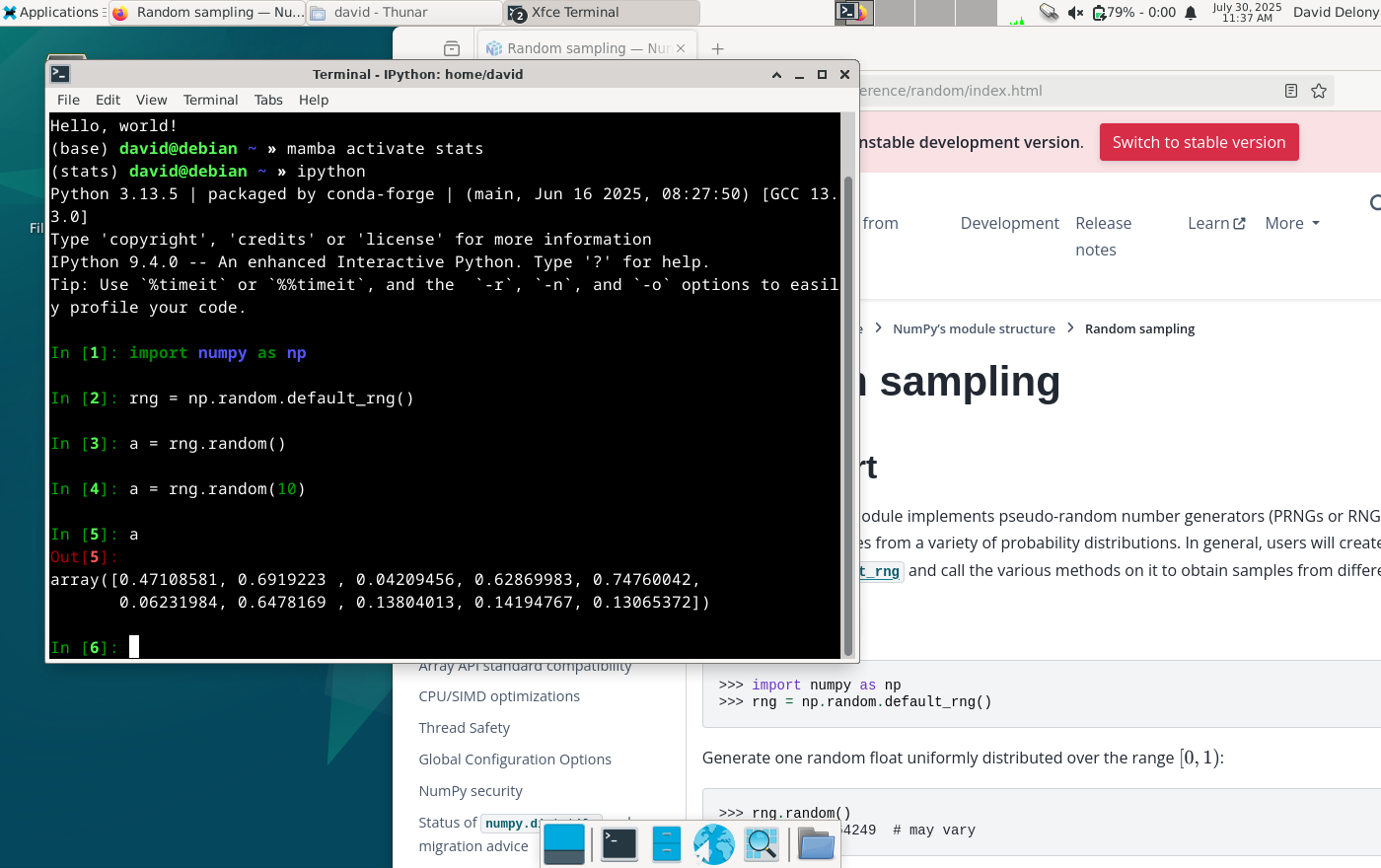

One of my main uses for Python is statistics and data analysis. I mainly use interactive Python, particularly the IPython that I set up with my Mamba environment. I’ll also look at documentation, either within IPython or on the internet. If I want a record of what I’m doing, such as to share later, I’ll open a Jupyter notebook. Since I’m mainly working interactively, I don’t have much use for debuggers. I can usually troubleshoot any error messages immediately.

Using an IDE would mean installing components that I didn’t use. A debugger would mostly be wasted for what I’m doing. And so would a full-blown IDE.

I Can Switch Out Apps When I Want To

A lot of developers tout the fact that integrated development environments are, well, integrated, including essential tools like editors, compilers, debuggers, and other things like linters and error checkers. In Linux, I can install editors, compilers, debuggers, linters, and error checkers through my package manager.

I’m not limited to what the IDE developer thought to include. If I don’t like the editor, I can just switch to a different one. I’ve become quite comfortable with Vim. The keystrokes do seem to feel better, at least on the chiclet keyboards that laptop manufacturers seem to favor these days.

One tool that I switched out was the Python interpreter. The Python interpreter is useful on its own since I can test out code ideas (and use it as a calculator), but IPython is even better, since it features syntax highlighting and easy recall, as well as the ability to run system commands right from IPython.

I was also able to switch out the package manager itself for Mamba. Mamba is optimized for data analysis and data science, offering newer packages in many cases than the system package manager, and letting me leave the system Python alone.

A standard IDE would likely not offer me this kind of flexibility.

If you use Linux or program for long enough, you tend to form opinions on the way things should work. One of those things that lots of people, including me, get opinionated about is the text editor. I tend to favor Vim, even though I went through an Emacs phase for a while, so I do have experience with both major editors.

The IDE approach is still popular, even among environments that aren’t considered IDEs. Emacs fans often cite how they can run tools like terminals or file browsers without having to leave the editor. I’ve never been that impressed with that aspect. This may be because I’ve almost always had access to windowing environments and done most of my programming work on platforms where launching processes is easy.

Emacs was originally designed for character-based terminals. It wasn’t easy to launch new tasks on these terminals, which is why there was an incentive to build a program where you could have everything you needed in one place.

If you use an IDE, you’re often stuck with what the developers thought you would want. Linux IDEs are popular, so I suppose there are a lot of people who want what they offer. Maybe my needs are just different than other people’s. Other developers can keep their IDEs, but I’ll be happily using multiple programs.

I’ve developed a comfort with the tools I use. When I move to a new system, I can set it up quickly and be in a familiar environment.

I Prefer to Multitask With Multiple Programs

I think I might just prefer the “Unix Philosophy” approach when it comes to development. This is an effect of the design of Unix-like operating systems making launching new processes easier. It’s easier in the sense that I can launch a new terminal and run a command easily. If I want an editor, I just run Vim. If I want to launch an interactive Python session, I launch my Mamba environment and open up IPython.

This is a consequence of the design of Linux and other Unix-like systems, as I mentioned earlier. Linux launches processes easily, while doing so on Windows has typically been a more resource-intensive process. When you’ve launched your program in such a system, threads are less expensive in terms of performance. This is the reason that there is a drive to stuff more functionality into a bigger program than the traditional Unix approach of one program that does one task.

The only problem was the user interface. Even though Unix was designed to be multitasking, it was awkward to switch between tasks. Job control and virtual consoles helped solve this problem, but it was with the availability of window systems running on workstations and graphical terminals that the approach of running multiple programs in individual windows became viable. Alternatively, terminal multiplexers can do a reasonably good job, especially on remote connections.

Related

Terminal Multiplexers Explained, and Why You’d Use One

Keep your SSH sessions going and going.

With the availability of multiple terminal windows, tabbed terminals, and terminal multiplexers available, I can take full advantage of this lightweight style of development. I can run my interactive Python session in one window for experimentation, a Jupyter notebook in my browser, and an editor in another window.

Using multiple apps on Linux may be less “integrated,” but this approach works for me without the overhead of a full-blown IDE. I think my effort pays off in a lightweight programming environment I can rely on.